Alternative Futures & Popular Protest, 2022 Final Programme

Please see the final version of the programme below; click titles to see abstracts and keywords. All sessions will run via Zoom, with Monday’s plenary roundtable being a hybrid event based on the University of Manchester campus. To access Zoom details for the conference, please register here.

Note: all times are in British Summer Time (= GMT/UTC+1).

Jump to: Monday PM, Tuesday AM, Tuesday PM, Wednesday AM, Wednesday PM

Monday 13th June

13:30 – 13:45 Welcome

13:45 – 15:15 Simultaneous Session 1

Session 1A

María Florencia Langa - Nature as a Moral Concept. How Morality Matters in Environmental Activism

Camilo Tamayo Gomez - Understanding the 2021 Colombian protests: places, spaces, and bodies of resistance and solidarity

One of the main characteristics of these protests was the involvement of diverse urban and rural constituencies in a single national protest, where young people made up the core of the demonstrations. In Colombia’s history of protest, the 2021 mobilisations are the most serious public unrest in recent memory. According to Human Rights Watch (2021) and Amnesty International (2021), 68 deaths occurred during the four months of demonstrations. The principal responsible of have committed these killings against mostly peaceful demonstrators are the members of the Colombian National Police.

In this context, this paper aims to analyse how the 2021 Colombian protests can be understood as an act of social disobedience. It will explore how the intersection between the symbolic reconfiguration of public spaces (streets, squares, public roads) during the protest, and the impact of police violence on demonstrators’ bodies, is showing new dimensions of social disobedience where the body becomes a place of resistance and the public space a site of civic solidarity.

Tim Weldon - Being Autonomous’: A squatting collective’s quest to build community

My ethnographic work centers on these questions as they pertain to Leftist inspired political projects, such as Klinika, and how ‘autonomy’ – as a core ‘governing’ principle – was practiced every day by individuals within the space, and how these practices led to unpredictable and spontaneous practices which created a specifically fluid and autonomous system of social interaction in the community.

This paper, rather than focus on broader more collectivized notions of ‘autonomy ‘from’ or ‘in relation to’ others and what this could mean for individuals – as many other studies have done – starts from the ground up with how individuals enact autonomy, and what social dynamics and collective practices are created within a larger community.

Ultimately, I briefly trace the fluidity within which activists organized and used space; obtained, re/upcycled, used, and ‘propertied’ ‘things’; created these ‘autonomous’ social dynamics; used consensus decision making to fortify their personal autonomy; and conclude be claiming that ‘autonomy’ – as seen within my informants’ understandings, actions, and collective practices within the space were more akin to anarchist, feminist, and eastern philosophical/Daoist understandings of personal and integrated autonomy than to the atomized autonomous selves of ‘Western’ philosophical discourse.

Hans Pruijt - Urban squatting, a SWOT analysis.

The following strengths are discussed: squatting is multifunctional, always serves a practical purpose, is empowering, less ephemeral than a demonstration or an occupation, offers self-sufficiency (because success is not dependent on the authorities taking notice and responding to demands), has disruptive qualities, and can spawn its own movement, a squatters’ movement, that can support and propel it.

Weaknesses are that squatting potentially involves personal risk and can attract repression. Two models of repression are distinguished: pragmatic tolerance and zero tolerance. Squatters tend to have a very weak legal position but there are loopholes which they can exploit.

Opportunities comprise helping poor people to housing, self-help housing, establishing a space for activities, or preservation of a building, function or neighborhood. The pursuit of any of these four categories can lead to the opening up of additional opportunities.

A key threat is the erosion of squatters rights, which involves criminalization, leading to de-legitimation and a weakened social institutionalization of squatting. A further threat is competition from the anti-squat industry. Finally, squatters can face criticism from the left for getting co-opted, or assimilated by the capitalist economic logic and by state actors.

Session 1B

Luke Yates & Kevin Gillan - Conceptualising social movement strategy

Kenny Chiwarawara - Protest leaders in mobilising and demobilising protests in South Africa: the case of Gugulethu and Khayelitsha, Cape Town

Andre Luis Sales - Brazilian Prefigurative Ativismo: a collectividual autonomist strategy

Laurence Cox - Learning needs for social transformation: a research strategy for social movement education

The Movement Learning Catalyst project, involving three established movement training networks and engaged academics, aims to tackle at least part of the problem through bringing together experienced activists and popular educators from different social movements across Europe in a year-long blended learning (online and residential) course offered part-time on a solidarity economy basis, “learning from each other’s struggles”.

The course will be geared towards developing strategic thinking and the skills needed to build alliances across organisations within movements, between different movements and communities in struggle, intersectionally within movements, transnationally and translocally. Regional, language-based groups and the possibility for modular participation will help to develop a network among participants, while the curriculum and resources will be made available open-access for movements and popular educators to use.

But what do activists need to know? This paper outlines the research strategy underpinning the course, involving the analysis of pre-existing data sets, interviews with peer organisations, focus groups with experienced activists and adult educators, and a community of inquiry accompanying the process. The hope is to identify activist learning needs that can make a real contribution to developing broader movements and deeper alliances bridging the divides of class, race, gender etc., the different ways movements are organised across countries and the boundaries between movement identities.

Session 1C

Máté Szabó - Relevance of the model of council democracy (Räterepublic) for contemporaray social movements

Kate Alexander - Building a social movement in the context of a pandemic and disintegrating state: Johannesburg’s Community Organising Working Group

Cosimo Pica - The “Union Comunera” and the communal state in the revolutionary process of transition beyond capital in Venezuela

Jacqueline del Castillo, Y. Bhatti, & M. Harris - How social movement organizers make sense of social movements for health and care

Session 1D

Hamid Rezai - Oppressive State and Authoritarian Opposition: Diffusion and Contraction of Social Protest in Iran, 1979-1989

Zitian Sun - The “V” in Nonviolence: Repressions, Justifications, and Responses in the 2019 Hong Kong Protest

Ji-Eun Ahn - “Let’s Hold Candles!”: The Routinisation of the Candlelight Vigils in South Korea

Benjamin Abrams - The New Resistance Movements: Regime Subversion and its Barriers in Democratic Societies

Ishika Seal - The Mothers of Manipur Protest: A case of unruly politics

15:15 – 15:30 Comfort Break

15:30 – 17:00 Plenary Roundtable

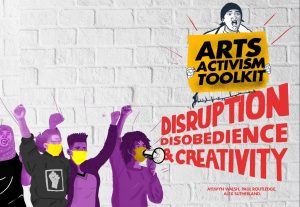

Disruption, Disobedience and Creativity

Chair: Aylwyn Walsh & Paul Routledge;

Chair: Aylwyn Walsh & Paul Routledge;This roundtable brings together scholar activists and arts activism practitioners to discuss the role of arts activism in the current conjuncture marked by the convergence of economic, social, political and ecological crises.

Disruption, Disobedience and Creativity

This roundtable brings together scholar activists and arts activism practitioners to discuss the role of arts activism in the current conjuncture, one marked by the convergence of economic, social, political and ecological crises. It coincides with the launch of the Arts Activism Toolkit, that emerged from #ImaginingOtherwise – a recent AHRC funded project on participatory arts education for social change in South Africa.

The toolkit is framed in part around key ‘R’ terms, which are used in this roundtable to pose key questions concerning the intersection of disruption, disobedience and creativity.

- How can relationships generate critical interpersonal resources needed for activists to be able to work together creatively over time?

- Which cultural repertoires are effective in creating protest cultures and identities; conveying emotions; transmitting protest actions, ideas and demands; and generating solidarity?

- How can reframing be deployed to pose, and make attractive, alternative futures?

- How might different types of arts-activism generate both recognition and resonance in different opponents and audiences in order to challenge dominant ideas, practices and stories?

- Which protest rituals are effective in challenging of norms and taboos – of both activists and society at large?

The toolkit is available for the conference delegates here.

Note: This event will be hybrid format, based on the University of Manchester campus and on zoom. It is open to the public for free, but registration is required. AFPP delegates should register if attending on campus, non-delegates can also register. Please register via Eventbrite.

Roundtable Speakers

https://www.daniabulhawa.com/

Tuesday 14th June

09:30 – 11:00 Simultaneous Session 3

Session 3A

Kyle Matthews - Radical Theories of Change and the New Zealand Climate Movement

Eloise Harding - The theory and practice of new environmental movements

James Goodman - Social Movements and Climate Change: Climatised ‘Movement Society’?

Daryl Tayar - (Re)connecting with self, community and the natural world: The motivation of climate and ecological emergency arrestees

Peter Gardner, Tiago Carvalho & Maria Valenstain - Spreading rebellion?: The rise of Extinction Rebellion chapters across the world

Session 3B

Shilpa Sharma - Shaheen Bagh protest and the rise of resistance by subaltern Muslim women in India

Akhaya Kumar Nayak - Gender and perceived identity in socio-religious protests: Two contrasting cases from India

Kyoko Tominaga - Who Meets the Perfect Standard of a ‘Real’ Feminist?: Writings by Feminist Activists in Japan

Kai Heidemann & Julia van Zijl - Pathways of Feminist Empowerment: Community education and free spaces in the Netherlands

Grzegorz Piotrowski & Magdalena Muszel - Polish women’s activism in Great Britain.

11:00 – 11:15 Comfort Break

1:15 – 12:45 Simultaneous Session 4

Session 4A

Martin John Greenwood - Erotic, Auratic and very democratic: A utopian reimagining of public services via Herbert Marcuse and Walter Benjamin

Albeniz Tugce Ezme Gurlek - Possibility of Reading Old Neighborhood Habits Growing in Mass Housing as a Resistance Against Apartment Life

Alexandrina Vanke - The creative forms of resistance: overcoming life difficulties in industrial neighbourhoods

Núria Suero Comellas - Social choirs and collective action

Session 4B

David Bailey - Comparative approaches to assessing movement effects: lessons from worker-led dissent in the British age of austerity

Simin Fadaee - Marxism, Islam and the Iranian Revolution

Jack McGinn - Myth as Mobiliser in the Early Syrian Revolution

Jann Boeddeling - From “Spontaneity” to Self-Activity: Reviewing the Study of Revolution through the case of Tunisia in 2010/11

Session 4C

Laya Hooshyari - How psychology and especially critical approaches to psychology make connection to social movements?

Birgan Gokmenoglu - From the “Spirit of Gezi” to the “Ills of Gezi”: Activist Self-Reflexivity and the Question of Organization in Grassroots Politics in Istanbul

Karla Henríquez - #ChileDespertó. Becoming actors of change

Sophia Wathne - Social Movements Prefiguring Political Theory

12:45 – 13:45 Lunch Break

13:45 – 15:15 Simultaneous Session 5

Session 5A

Carys Hughes - Governing to raise consciousness. What does ‘left governmentality’ look like?

Peter Ramand - From Class Analysis to Real Utopias and Back Again: Erik Olin Wright in Conversation with Left Populism

Mike O’Donnell - Looking Back to the Futures of Populism

Uri Gordon - Leviathan’s Body: Recovering Fredy Perlman’s anarchist social theory

Session 5B

Claire Crawford - The Movement and its Fragments: Considering social movements through postcolonial theory

Chungse Jung - From Semiperiphery to Strong Periphery: Transforming Epicenter of Antisystemic Movements in the Global South

Federico M. Rossi - Capitalist Dynamics and Social Movements

Ben Manski - Systemic movements, next system studies, and the other world that is possible

Session 5C

Johan Gordillo-Garcia - Social movements and political-emotional communities. An approach from the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity in Mexico

Mariam Kalandadze - Dynamics of Standing with Ukraine: Injustice Frame and Emotions in Solidarity Protests in Georgia

Geoffrey Pleyers - Shifting the analysis of confluence in social movement studies: From organisations and frames to activist cultures

Alexandre Christoyannopoulos - Pacifism and Nonviolence: Delineating the contours of a new research agenda

Session 5D

Josh Bunting - Where the People Rule: Decolonising Democracy and Decentering Western Liberalism

Soumodip Sinha - Protest as ‘capital’: a digital ethnography of student political activism amid the Pandemic

Louis Edgar Esparza Aditi Sapra - Teaching the Sustainable Development Goals

Rajeev Dubey - Public Sphere, Student activism and Democracy in India

15:15 – 15:30 Comfort Break

15:30 – 17:00 Plenary Roundtable

Chile: Towards a Laboratory of Social Change?

Chair: Ivette Hernandez Santibañez

Chair: Ivette Hernandez Santibañez

Chile: Towards a Laboratory of Social Change?

For the last two years, Chile has been on its path towards historic changes that make the possibility that the country, which has been widely acknowledged as the first laboratory of neoliberalism, also become the place where neoliberalism will die. In October 2019, large-scale protests across the country, known as the Estallido Social, emerged to fight injustice and inequality, and opened up the political opportunity to replace Pinochet’s constitution through a fully elected constitutional assembly with gender parity and set quotas for Indigenous people’s delegates.

Last December 2021, Gabriel Boric, a former student leader, was elected as Chile’s president. Boric’s victory could be seen as the legacy of the Chilean student movement that provided a framework to understand this shift. Gabriel Boric is part of a radical generation of student leaders who were catapulted into the spotlight during the 2011 Chilean student protests that demanded a radical reform of the Chilean neoliberal market-driven education system. In 2013, the election of four former student leaders, including Gabriel Boric, as MPs gained international attention as it was interpreted as providing hope to dismantle the system from within.

This panel will reflect on the legacy of the Chilean student movement to pave the way for Boric’s promise to bury the legacy of the neoliberal economic model once and for all comes true. It addresses questions about the nature of radical changes in politics led by the Chilean student movement. It debates the legacy of the Chilean student movement to reframe a new relationship between social movements and the government to either transform or prompt a new model of democracy. The panel will also discuss the legacy of the Chilean student movement in the current constitutional process, reflecting on how the demand for free public quality education ended up paving the path towards a laboratory of social change in Chile.

This is a fully online event. It is open to the public via registration at Eventbrite. AFPP delegates do not need to register separately.

Speakers:

Wednesday 15th June

09:30 – 11:00 Simultaneous Session 7

Session 7A

Tomas Pewton - An Alternative Food System

Juliette Wilson-Thomas - Time’s up: Analyzing the feminist potential of time banks

Leonie Guerrero Lara, Julia Spanier & Giuseppe FEola - A one-sided love affair? An empirical study on the potential of a coalition between the Degrowth and Community Supported Agriculture movement in Germany

Session 7B

Dustie Spencer & Ritumbra Manuvie - Are Antifeminists Swallowing the Same Black Pill? Transnational Discourse in Asia’s Manosphere

Mert Büyükkarabacak - Recasting the Class Conflict

Matthijs Gardenier - Anti-migrant mobilisations around Channel Small Boat crossings

Hilary Darcy - Responsive or creative community and workplace approaches to counter the rise of the far right? Strategy dilemmas of social movements in Ireland and beyond.

11:00 – 11:15 Comfort Break

11.15 – 12:45 Plenary Roundtable

Chile: Towards a Laboratory of Social Change?

Chair: Ivette Hernandez Santibañez

Chair: Ivette Hernandez Santibañez

Chile: Towards a Laboratory of Social Change?

For the last two years, Chile has been on its path towards historic changes that make the possibility that the country, which has been widely acknowledged as the first laboratory of neoliberalism, also become the place where neoliberalism will die. In October 2019, large-scale protests across the country, known as the Estallido Social, emerged to fight injustice and inequality, and opened up the political opportunity to replace Pinochet’s constitution through a fully elected constitutional assembly with gender parity and set quotas for Indigenous people’s delegates.

Last December 2021, Gabriel Boric, a former student leader, was elected as Chile’s president. Boric’s victory could be seen as the legacy of the Chilean student movement that provided a framework to understand this shift. Gabriel Boric is part of a radical generation of student leaders who were catapulted into the spotlight during the 2011 Chilean student protests that demanded a radical reform of the Chilean neoliberal market-driven education system. In 2013, the election of four former student leaders, including Gabriel Boric, as MPs gained international attention as it was interpreted as providing hope to dismantle the system from within.

This panel will reflect on the legacy of the Chilean student movement to pave the way for Boric’s promise to bury the legacy of the neoliberal economic model once and for all comes true. It addresses questions about the nature of radical changes in politics led by the Chilean student movement. It debates the legacy of the Chilean student movement to reframe a new relationship between social movements and the government to either transform or prompt a new model of democracy. The panel will also discuss the legacy of the Chilean student movement in the current constitutional process, reflecting on how the demand for free public quality education ended up paving the path towards a laboratory of social change in Chile.

This is a fully online event. It is open to the public via registration at Eventbrite. AFPP delegates do not need to register separately.