Staging protest’s relics: a visit to Disobedient Objects at the V&A

‘How might an object be disobedient?’ The question occurred to me throughout the morning before my visit to the V&A. The exhibition’s title on the one hand seemed to allude to the truth that items and materials are part of our networks of contention, but it seemed to go further, lending an agency to those items, the apparent distinction between objects and disobedient subjects blurred. On arriving at the exhibition, the blocks of text, interspersed throughout, continued this tone, telling visitors that ‘objects can cement a movement’ and ‘objects can act as ambassadors’.

‘How might an object be disobedient?’ The question occurred to me throughout the morning before my visit to the V&A. The exhibition’s title on the one hand seemed to allude to the truth that items and materials are part of our networks of contention, but it seemed to go further, lending an agency to those items, the apparent distinction between objects and disobedient subjects blurred. On arriving at the exhibition, the blocks of text, interspersed throughout, continued this tone, telling visitors that ‘objects can cement a movement’ and ‘objects can act as ambassadors’.

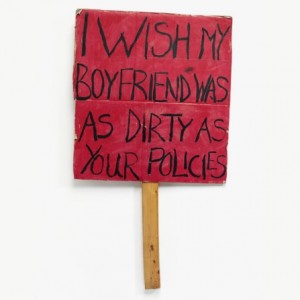

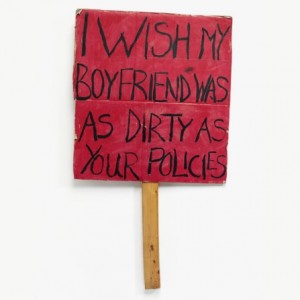

In only a small side gallery, the exhibition contains a decent collection of the objects of protest, campaigning, and insurrection: saucepan lids beaten bent in the Argentine cacerolazo; the red felt square patches of the Quebec student movement; Zapatista dolls; defaced currencies; smartphone carrying drones from the Spanish 15M; Black Panther prisoner crafts; newspapers and leaflets; a wall of book bloc shields; placards; banners; pin badges. These are objects as tactical tools, as markers of membership and solidarity, as conveyers of text, and as souvenirs.

The risk of course, common to much museum work, is the abstraction of these objects from their context. When is a slingshot not a slingshot? Maybe when it is pinned – geometrically, deliberately, stationary – behind a glass case. Like the slingshot, these frozen objects, united under the shared rubric of ‘protest’ can become transmuted into different objects entirely (displays), as the environments, networks and assemblages in which they had made sense are long gone.

Given its home in the V&A, it is unsurprising that a logic of ‘design’ undergirds the presentation of the objects. On one board of text commentary we are told movement participants are ‘driven to out-design authority using imagination and creativity’. This in turn taps into the exhibition’s wider tendency to present protest and social movement as the activity of rational actors mobilising resources based on calculation, and using creative design to even up the power difference between protesters and the police, or the state. To be sure, there are plenty of objects to support this notion of the activist as rational designer, like the inflatable cobblestones designed to playfully confound the Berlin police in 2012. But it can be a rarefied picture of design; on the way into the exhibition space, we are told that the design of angular, metal barricades was the model used for the construction of the exhibition’s entrance. Strange barricade.

At one point the accompanying text asserts that ‘there is no protest aesthetic’. Indeed, the breadth of materials, types of labour, and sense of style behind the many objects results in a varied sensory experience. But this is very much an aesthetic event. The display cases made of chipboard and exposed brushed chrome piping, have a thrown-together look, which follows the presentation of the whole, giving the lie to the claim that there is no common aesthetic. The curation instead suggests that this is a sort of ‘people’s aesthetic’. It is naïve, and rushed and knocked together from what they had. Frequently it is the work of many hands. All this stands in stark contrast with the classical busts and statues in the open atrium through which you enter the exhibition.

The aesthetic experience of Disobedient Objects is one of auras, similar to those outlined by Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1955 [1936]). For Benjamin, the museum trades in the singular irreproducible experience of encounter between the subject/visitor and the auratically-charged, original object. It is a near mystical effect of authenticity and presence. This is the condition of the ‘disobedient objects’ of the exhibition, as framed most notably by the narrative film projected on the back wall, which hammers home their role in moments where the wheel of history was turned. Removed from those contexts, the objects are elevated as icons – relics even – with the traces of capital ‘H’ History still on them.

I thought this, wandering amongst the exhibits. I thought how odd it was that these objects were being consumed in much the same way as authored bourgeois artworks, even those that were clearly the result of the labour of many anonymous, marginal hands. I watched the visitors, peering at their relics, and thought how silly! And then I looked up. Strung across the ceiling – partly obscured and out of the way – was a large banner, pink on green, reading ‘Capitalism Is Crisis’. This banner, originally from the Blackheath Camp for Climate Action in 2009 had later, in October 2011, been hung above the tents of Occupy the London Stock Exchange outside St Paul’s Cathedral, an event in which I participated actively, and one which sparked an intensification of my own activism, and ultimately my current PhD research. Any wry cynicism of the auratic spectacle went out the window and I stood beneath it transported, lost in memories and interview quotes of the moments for which that banner had formed the backdrop. This was maybe a different magic to Benjamin’s, but it was a conjuring of sorts. Later I bumped into a friend who had been involved in Reclaim the Streets in the late 90s; he was edging eagerly to get close to a copy of the Evading Standards newspaper he had distributed at the J18 Carnival Against Capital in 1999.

There has clearly been considerable contributions from activists and campaigners in constructing the exhibition, and their accounts of the objects in context, as well as their wider claims about the role of civil disobedience and collective action in social change is vital to the successes of Disobedient Objects. But this is not an activist intervention in the museum. It is instead a sometimes moving, sometimes crass, always aesthetic and auratic, staging of the broad concept of ‘protest’ as it relates to ‘design’. It stands and falls with the limits of that framework.

Disobedient Objects runs at the Victoria and Albert Museum until 1st February 2015.

Jamie Matthews

Jamie Matthews is a final year PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Manchester. Jamie’s PhD thesis is a critical ethnography of Occupy London, focusing on questions of ideology, identity, and social movement spatial practice. The project emerges from his own participation in Occupy.

0 Comments